Everyone is blogging and posting about pizza today: free pizza, pizza recipes, pizza challenges abound. So I thought I’d give you some West Virginia Italian history to chew on while you’re enjoying your pie. Italians have a rich history in West Virginia. In fact, they made up 30% of the immigrant population at the turn of the 20th century. [1] Although many were employed in the coal mines, there were folks like Alessandro Moretti who worked in glass and brought an ages-long history of glass-making with them sharing their knowledge with members of the local population, passing on the torch or a rich tradition, many elements of which were lost to history before Moretti arrived in the US. Moretti was born in 1922 and died in 1998. I found this obscure auto-biographical note by Moretti in a web search [3]:

"500 years after the birth of Christ, my Venetian ancestors gained control of the glass industry and became the leaders in the manufacture of glass. The Venetians perfected the glass by adding minerals and pebbles (found in their rivers) to the glass silica. The Venetians were also credited with perfecting clear glass known as "cristallo." Further, they were credited with making the finest coloured glass by adding assorted "oxides" to the silica to achieve colours of extraordinary splendor. On the island of Murano, (which was the glass center of the Venetian industry), glassmakers were considered "royalty," and had certain democratic privileges, but in exchange for such titles and privileges, the government in an attempt to protect the secrets of the glass trade, imprisoned and confined these glassmakers to the Island of Murano. If one of these workmen attempted to leave the island to practice their craft elsewhere, they were condemned to death for treachery. This practice was initiated by the Republic of Venice in order to keep control and monopolize the industry of glassmaking. There was a period when a large part of Venice was destroyed by glasshouses catching on fire. Therefore, Venetian authorities moved all of the glasshouses to the "Island of Murano", which was located on a lagoon outside of Venice. By doing this, the Venetians not only protected Venice from the hazards of fire, but also insured government regulation and State protection. Historically, I come from a long bloodline of Morettis directly related with the glass industry on the Island of Murano. This descendance prompted me to be a glassworker. The history of the Moretti family is inscribed in "The Gold Book," which is maintained at the famed "Museum of Glass" in Murano. I remember, when I was a small boy, after school, I would always stop at the glasshouses on my way home to gaze into the windows of these factories. I would watch the glassworkers and Maestros of that time work the glass. As my father was also a glassblower, I guess I grew up in the industry and was influenced and fascinated by it. I must have been ten years of age, when I mentioned to my mother that, when I was old enough, I wanted to become a great glass maestro. My mother was very encouraging and prompted me to pursue my goal. With the onslaught of World War I, glass production came to a halt! When my father returned from military service after the war ended, the glass industry sluggishly started making a comeback. I guess I must have been 13 years of age when I applied with a small factory as a helper and they hired me. I had just graduated the 5th grade. This factory produced small blown "objects of utility" and as I got older and more knowledgeable, I became more interested in learning about "artistic" and "ornamental" glass, so when I became of age, I transferred to the acclaimed "Seguso" factory, which specialized in "artistic glass." This factory employed some of the foremost Maestros of that time, and I was fortunate to be able to train with some of its finest "teachers", such as Aldo Toso, Artilio Frondi and Nino Pavanello. A number of years later, I received a proposal to transfer to the "Mazzega" glass factory, along with my Maestro, Nino Pavanello. This factory was larger and more lucrative than the Seguso factory, wherein I had initially been trained. In this factory, under the guidance of "Maestro Pavanello", I finally achieved the coveted title of "Maestro". I was 26 years of age; one of the youngest Maestros ever to receive such a coveted title. In 1950, the historically acclaimed "Venini" artglass factory invited me to join their team of highly specialized artists as their "Maestro of Figurines and Chandeliers". Certainly, it was a great honor--that they recognized my capabilities in the field of coloured glass and figurines and I accepted their offer. As a coveted "Maestro" at the Venini Factory, I became blindly content in Murano... Eventually, I felt "restrained" and began feeling as if I were a prisoner on this island. I wanted to leave Murano in order to pursue my own style of creating artglass. I did not want to be influenced by the ideas of other artists... but it was not that easy... History evidences that Maestros and glass artisans "with too much knowledge" could not leave so easily and after receiving employment opportunities from numerous countries abroad, I found that my Visa had been "blocked". WWII had ended... and I refused to be "restrained" -- they could not hold me here against my will. I found a proposal from an entrepreneur in South Africa to be most interesting, (as I was requested to pioneer the formation of the "first glass factory" ever established in the City of Johannesburg, South Africa). After careful consideration, I chose to accept this offer and my Visa to leave the country was finally approved; I emigrated to this continent in 1951, taking with me the only thing I knew best--the art of glassmaking. Soon after my arrival, I met and eventually married my Genovese wife, Lidia Villa. My wife also had escaped a war-ravaged italy to find a better life abroad. (Her immediate family consisted of her mother, Emilia Villa, who was a WWII medical nurse; her step-father, Armando Corpetti, and my wife's only sister, Tamara Mafalda Villa --who was employed by the Italian/German Embassy as a multi-linguist during WWII; her birth father, Vicenzio Villa, became a young casualty of pneumonia just prior to the onslaught of WWII and died at the tender age of 32. He was an Alpine soldier. With all the unsavory memories behind me, I actually enjoyed my life in South Africa. However, my dream had always been to immigrate to the United States, and in 1956, the opportunity presented itself and I transferred with my wife to the center of glassmaking in West Virginia. Initially, I experienced some difficulty with the language, (even though I did have some experience with the English language in South Africa). However, the greatest difficulty was not the language, but the lack of a suitable helper who was used to my manner of working the glass. In time, I was able to train my co-workers in the art of apprenticeship and the dilemma of a suitable helper was lifted. My co-workers were eager to learn as much as they could of what I had learned as a child in Italy. Then I was blessed with my brother, Roberto, joining me in the United States in 1958. During the last 34 years that I have been in this country, I feel fulfilled with my accomplishments; and I feel that the United States is the most incredible place in the World. In 1964-65, I was invited to participate in the New York World's Fair, where I was honored to exhibit my craft at the "West Virginia Pavillion" sponsored by the Pilgrim Glass Company. After the New York World's Fair, I enjoyed displaying my creations in craft shows and gallery exhibits. (This interview - 1990, prior to Alessandro's demise on December 3, 1998). I want to thank my daughter, Yvonne, for bringing forth the production of this short biography, and my talented eldest son, Franco, who is the last lineal descendant of my familial line, who continues the glass trade in Murano, Italy. My youngest son, Albert chose not to carry on the legacy of glassworks and is successful in the auto repair business. In closing, my hope is that mankind will not let this millennia old artform "die" and that fathers will continue to preserve this 3000 artform by passing its secrets to their sons, as I have to my eldest son, who continues my legacy on the "Island of Murano".”

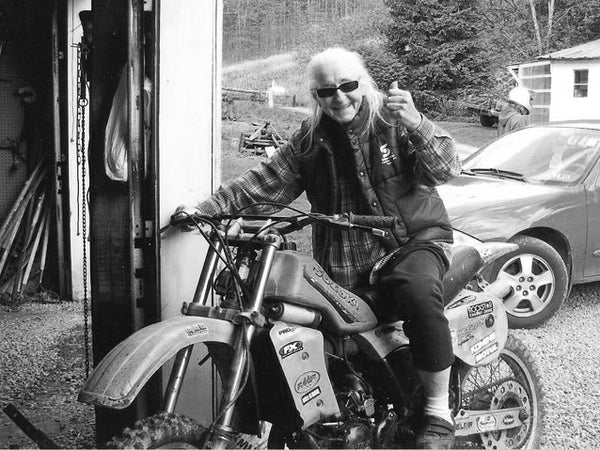

I find stories like Moretti’s to be so inspirational because he followed his passion nearly to all ends of the earth, and hoped that future generations would carry on a tradition that he so loved, knowing that if not, his artform could be lost. His story actually reminds me a bit of Dot Montgillion’s, founder of Smoke Camp Crafts, and having learned many aspects of the age-old crafts of herbalism and gardening from her, I am tasked with ensuring that future generations carry on the work that I’m doing today.

So, in honor of National Pizza Day, all things Italian and future generations, I’m celebrating several of my favorite herbs used in Italian cooking to experience the taste of tradition!

Basil, Ocimum basilicum, is invariably the first herb that comes to mind when one thinks of Italian cuisine, as it’s used in the Caprese salad and most famously Italian pesto sauce. The Caprese salad is typically made with tomatoes, fresh mozzarella, fresh, thinly sliced basil and a drizzle of extra virgin olive oil. I also like to add a dash of tarragon and sea salt. An excellent West Virginia twist on pesto sauce, traditionally made with pine nuts, is to use black walnuts instead. As it’s National Pizza Day, I should probably mention the Margherita pizza which is basically a Caprese salad baked onto pizza dough. We offer dried basil for sale, which is great in the middle of winter, but to truly experience these recipes, you’ll want to use freshly picked basil from your garden or a container planter next to a window in your kitchen. We have seeds and will soon have plants available for sale.

Fennel, Foeniculum vulgare, is the plant that produces the seed used to flavor Italian sausage and Italian sweet Easter bread. Angelo’s Old World Italian sausage is the best in West Virginia, and no doubt do they use fennel to flavor their links.

Oregano, Origanum vulgare adds an herbal punch to pizza and pasta sauce and is the ultimate herbal compliment to the tomato. It is a also a hardy perennial so plant it once and you can enjoy the flavor it provides for years to come.

Flat-leaved Parsley, Petroselenium crispum can actually be used to make a really tasty, non-traditional pesto sauce by blending parsley, lots of garlic and olive oil.

[1] Barkey, Fred A. "Italians." e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 29 March 2011. Web. 05 February 2022.

[2] Italians in West Virginia by Victor A. Basile and Judy Prozzillo Byers

[3] http://morettiglas.20fr.com/index.html